DATO’ SERI ANWAR IBRAHIM v. PP & ANOTHER APPEAL

FEDERAL COURT, PUTRAJAYA

ABDUL HAMID MOHAMAD, FCJ; RAHMAH HUSSAIN, FCJ; TENGKU BAHARUDIN, JCA

CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS: 0562003 (W) & 0572003 (W)

2 SEPTEMBER 2004

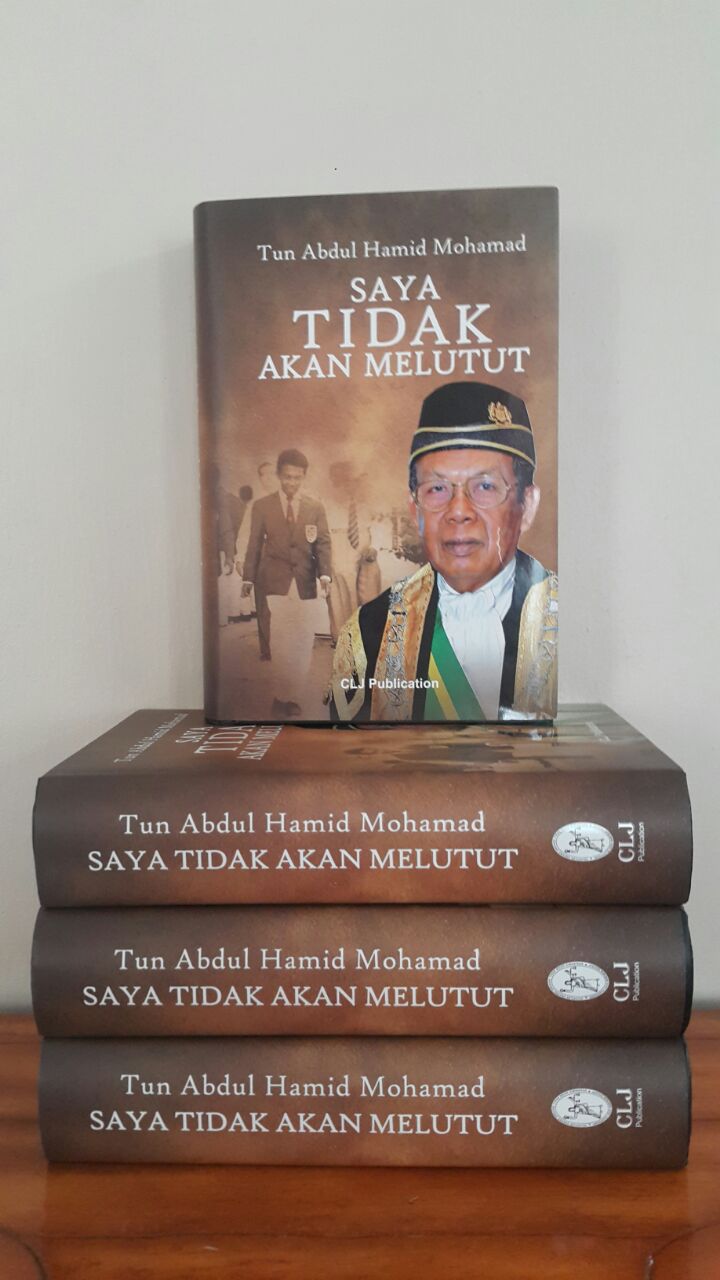

[2004] 3 CLJ 737

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE: Charge Sexual offence Date of offence as charged Whether proved

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE: Conviction Validity of conviction Conviction grounded on evidence of witness Witness, whether credible Date of offence, whether proved Accomplice, whether witness is Corroboration, whether required

EVIDENCE: Accomplice Whether witness is

EVIDENCE: Corroboration Sexual offence Accomplice evidence Whether corroborated

EVIDENCE: Confession Circumstances leading to confession of accused Whether rendered confession inadmissible.

EVIDENCE: Witness Credibility of Inconsistent statements made Whether credibility affected.

CRIMINAL LAW: Penal Code Section 377B Committing carnal intercourse against the order of nature Conviction grounded on evidence of witness Witness, whether credible Date of offence, whether proved Accomplice, whether witness is Corroboration, whether required

There were two appeals before this court. In the first appeal, the appellant (‘the first appellant’), a former Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia, was convicted of an offence punishable under s. 377B of the Penal Code for committing carnal intercourse against the order of nature. He was sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment to commence after he served his sentence in respect of his conviction in an earlier trial for corruption. In the second appeal, the appellant (‘the second appellant’) was convicted on two charges preferred against him. The first charge was for the offence of abetment punishable under s. 109 read with s. 377B of the Penal Code whilst the second charge was for the offence punishable under s. 377B. He was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment with two strokes of whipping for the first charge and the same for the second charge. The sentences were to run concurrently. Both the appellants’ appeals against their convictions and sentences to the Court of Appeal were dismissed. Hence, their appeals herein.

The issues were: (1) whether one Azizan Abu Bakar (‘Azizan’) whose evidence the prosecution case relied upon was a credible witness; (2) whether the date of the offence was proved as charged; (3) whether Azizan was an accomplice and corroboration was required; and (4) whether the confession by the second appellant was voluntary.

Held (allowing the appeals and acquitting the appellants):

Per Abdul Hamid Mohamad FCJ (majority)

[1] Azizan gave contradictory statements as to the date of the offence. The fact that he was not impeached in the proceedings brought against him in respect of his contradictory statements did not mean that his whole evidence must be believed. His evidence should be scrutinised with care, bearing in mind the dent in his credibility caused by his contradicting statements. His evidence as a whole did not support the learned judge’s finding that he was wholly reliable, credible and truthful.

[2] The learned trial judge failed to look at the surrounding circumstances as to whether Azizan had the mens rea of an accomplice. Azizan gave evidence that he was sodomised 10 to 15 times at various places. He never lodged any police report. He continued to work for the first appellant. There was no evidence of any protest by him either. His submission that he acceded out of fear was also not substantiated. Accordingly, Azizan was an accomplice, though he might have been a reluctant one.

[3] The facts showed that there were unusual circumstances surrounding the arrest and the confession of the second appellant. As the first appellant, the former Deputy Prime Minister of Malaysia, was assaulted by the Inspector General of Police, it would not be much to expect that the second appellant would have been treated any differently during his detention. Further, the version given by the prosecution witnesses confirmed many of what the second appellant told the court except for the specific allegations denied by them. As such, the courts below failed to consider all the surrounding circumstances that led to the confession. This tantamount to a serious misdirection that warranted intervention herein. Accordingly, the confession was inadmissible.

[4] The question was whether the date of the offence was proved as charged. Section 153(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code clearly states that the charge shall contain such particulars as to the time. Since it is mandatory to state the “time “, (date or period) when an offence is alleged to have been committed, it is clearly a material matter and an essential part of the alleged offence. If the law clearly provides that the charge shall contain particulars as to “time “, it follows that such particulars must be proved.

[5] The only evidence available to prove the date of the commission of the offence was that of Azizan. He gave three different periods. His demeanor even prompted the learned judge to record that he was evasive and appeared not to answer a simple question put to him. On such evidence, it could not be accepted that the date of the offence was proved beyond reasonable doubt. Further, in considering his evidence, any benefit of the doubt should be given to the appellants who were the accused. The prosecution too was unsure of the dates when the offence was committed. Therefore, the date of the offence was not proved as per charge.

[6] As Azizan was an accomplice, corroborative evidence of a convincing, cogent and irresistable character was required. The testimonies of one Dr Mohd Fadzil and one Tun Haniff and the conduct of the first appellant confirmed the appellants’ involvement in homosexual activities. However, such evidence did not corroborate Azizan’s story that the appellants sodomised him at the date, time and place specified in the charge. In the absence of any corroborative evidence it was unsafe to convict the appellants on the evidence of Azizan. Furthermore, the offence was a sexual offence requiring corroboration. The prosecution therefore failed to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt.

[Bahasa Malaysia Translation Of Headnotes

Terdapat dua rayuan di hadapan mahkamah ini. Dalam rayuan pertama, perayu (‘perayu pertama’), bekas Timbalan Perdana Menteri Malaysia, telah disabitkan dengan kesalahan di bawah s. 377B Kanun Keseksaan kerana melakukan persetubuhan bertentangan dengan aturan tabii. Beliau telah dihukum sembilan tahun penjara yang berkuatkuasa selepas beliau menjalani hukuman penjara yang dijatuhkan terhadapnya dalam satu kes rasuah sebelumnya. Dalam rayuan kedua, perayu (‘perayu kedua’) telah disabit atas dua pertuduhan yang dikenakan ke atasnya. Pertuduhan pertama adalah kerana kesalahan bersubahat di bawah s. 109 dibaca bersama s. 377B Kanun Keseksaan sementara pertuduhan kedua adalah bagi kesalahan yang boleh dihukum di bawah s. 377B. Beliau telah dihukum enam tahun penjara dan dua sebatan bagi pertuduhan pertama dan begitu juga bagi pertuduhan kedua. Hukumanhukuman telah diperintahkan berjalan serentak. Rayuan perayuperayu ke Mahkamah Rayuan terhadap sabitan dan hukuman telah ditolak. Mereka dengan itu merayu seterusnya.

Isuisunya adalah: (1) sama ada Azizan Abu Bakar (‘Azizan’) yang mana keterangannya menjadi sandaran kes pendakwaan merupakan seorang saksi yang boleh dipercayai; (2) sama ada tarikh kesalahan sepertimana dalam pertuduhan telah dibuktikan; (3) sama ada Azizan adalah seorang rakan sejenayah dan memerlukan keterangan sokongan; dan (4) sama ada pengakuansalah perayu kedua diberi dengan rela hati.

Diputuskan (membenarkan rayuan dan membebaskan perayuperayu):

Oleh Abdul Hamid Haji Mohamad HMP (majoriti)

[1] Azizan memberikan kenyataankenyataan bercanggah mengenai tarikh kesalahan. Fakta bahawa beliau tidak dicabar tentang kenyataankenyataan bercanggah itu tidak bermakna bahawa keseluruhan keterangannya menjadi boleh dipercayai. Keterangannya perlu diteliti secara berhatihati, dengan mengambil kira bahawa kebolehpercayaannya telah terjejas oleh kenyataankenyataan bercanggahnya. Keterangan beliau pada keseluruhannya tidak menyokong dapatan yang arif hakim bahawa beliau adalah seorang yang jujur, boleh dipercayai dan bercakap benar.

[2]Yang arif hakim gagal melihat kepada keadaan sekeliling berhubung sama ada Azizan mempunyai mens rea seorang rakan sejenayah. Azizan memberi keterangan bahawa beliau telah diliwat sebanyak 10 15 kali di beberapa tempat. Beliau tidak pernah membuat apaapa laporan polis. Sebaliknya beliau terus bekerja dengan perayu pertama dan tidak ada keterangan yang menunjukkan bantahan dibuat olehnya. Katakatanya bahawa beliau terpaksa akur kerana takut tidak disokong oleh keterangan. Azizan dengan itu adalah seorang rakan sejenayah, walaupun beliau mungkin menjadi begitu dengan agak keberatan.

[3]Fakta menunjukkan bahawa penangkapan dan pengakuansalah perayu kedua diselubungi oleh keadaankeadaan yang luar biasa. Memandangkan bahawa perayu pertama, selaku bekas Timbalan Perdana Menteri Malaysia, telah dipukul oleh Ketua Polis Negara, bukanlah sesuatu yang luar biasa untuk menganggap bahawa perayu kedua tidak dilayan dengan cara berlainan semasa dalam tahanan. Selain dari itu, kecuali apa yang telah disangkal dengan secara khusus, versi yang diberikan oleh saksisaksi pendakwa mengesahkan apa yang diceritakan kepada mahkamah oleh perayu kedua. Oleh itu, mahkamah di bawah telah gagal mempertimbang keadaan sekeliling yang membawa kepada pengakuansalah. Ini adalah satu salah arahan serius yang mewajarkan campurtangan di sini. Ianya mengikut bahawa pengakuansalah tidak boleh diterima masuk.

[4]Persoalannya adalah sama ada kesalahan telah dibuktikan pada tarikh sepertimana yang dituduh. Seksyen 153(1) Kanun Prosedur Jenayah jelas memperuntukkan bahawa pertuduhan hendaklah mengandungi butirbutir mengenai masa. Oleh kerana ianya adalah wajib untuk menyatakan “masa ” (tarikh atau tempoh) bila sesuatu kesalahan itu dikatakan telah dilakukan, maka perkara itu adalah perkara material dan menjadi satu bahagian penting kesalahan. Jika undangundang dengan jelasnya mengatakan bahawa pertuduhan mesti mengandungi butirbutir mengenai “masa “, maka butirbutir tersebut mestilah dibuktikan.

[5]Keterangan yang ada bagi membuktikan tarikh perlakuan kesalahan hanyalah keterangan Azizan. Azizan memberikan tiga tempoh yang berlainan. Tingkahlaku beliau menyebabkan yang arif hakim merekodkan bahawa beliau bersikap mengelak dan kelihatan gagal menjawab walaupun soalan yang diajukan kepadanya adalah soalan senang. Atas keterangan ini, adalah tidak dapat diterima bahawa tarikh kesalahan telah dibuktikan di luar keraguan munasabah. Tambahan, dalam mempertimbang keterangannya itu, apa jua manfaat keraguan harus diberikan kepada perayuperayu sebagai tertuduh. Pendakwaan juga tidak berapa pasti akan tarikhtarikh bila kesalahan dilakukan. Oleh itu, tarikh kesalahan seperti dalam pertuduhan telah tidak dibuktikan.

[6]Oleh kerana Azizan seorang rakan sejenayah, perlu ada keterangan sokongan yang menyakinkan, yang kuat dan yang tak dapat ditolak. Testimonitestimoni Dr Mohd Fadzil dan Tun Haniff serta kelakuan perayu pertama mengesahkan penglibatan perayuperayu dalam kegiatan homoseksual. Bagaimana pun, keterangan tersebut tidak menyokong cerita Azizan bahawa perayuperayu telah meliwatnya pada tarikh, masa dan tempat seperti yang tertera dalam pertuduhan. Dalam ketiadaan apaapa keterangan sokongan, adalah tidak selamat untuk mensabitkan perayuperayu berasaskan keterangan Azizan. Lagipun, kesalahan adalah kesalahan seksual yang memerlukan keterangan sokongan. Pendakwaan dengan itu gagal membuktikan satu kes di luar keraguan munasabah.

Reported by Usha Thiagarajah

Case(s) referred to:

Ah Mee v. PP [1967] MLJ 220 (refd)

Attorney General of Hong Kong v. Wong Muk Ping [1987] AC 501 (refd)

Aziz Muhammad Din PP [1996] 5 MLJ 473 (refd)

Bal Mukundo Singh v. Emperor [1937] 38 Cr LJ 70 (refd)

Balasingam v. PP [1959] MLJ 193 (refd)

Bhojraj v. Sitaram [1936] ALR 60 PC (refd)

Chan Ming Cheng v. PP [2002] 4 CLJ 77 CA (refd)

Chean Siong Guat v. PP [1969] 2 MLJ 63 (refd)

Chin Nam Hong v. PP [1965] MLJ 40 (refd)

Clarke Edinburgh Tramways [1919] SC (HL) 35 (refd)

Dato’ Mokhtar Hashim v. PP [1983] 2 MLJ 232 (refd)

Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. PP [2003] 4 CLJ 409 CA (refd)

Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. PP [2002] 3 CLJ 457 FC (refd)

Director of Public Prosecutions v. Hester [1973] AC 296 (refd)

Director of Public Prosecutions v. Kilbourne [1973] 1 All ER 440 (refd)

Director of Public Prosecutions v. Ping Ling [1975] 3 All ER 175 (refd)

Dowse v. AttorneyGeneral, Federation of Malaya [1961] 27 MLJ 249 (refd)

Ganpart v. Emperor AIR [1918] Lab 322 (refd)

Goh Leng Kwang v. Teng Swee Lin & Ors [1994] 2 MLJ 5 (refd)

Hasibullah Mohd Ghazali v. PP [1993] 4 CLJ 535 SC (refd)

Herchun Singh & Ors v. PP [1969] 2 MLJ 209 (refd)

Ho Ming Siang v. PP [1966] 1 MLJ 252 (refd)

Hussin Sillit v. PP [1988] 2 MLJ 232 (refd)

Jegathesan v. PP [1980] 1 MLJ 167 (refd)

Kandasamy v. Mohamed Mustafa [1983] 2 MLJ 85 (refd)

Koay Chooi v. R [1955] MLJ 209 (refd)

Ku Lip See v. PP [1982] 1 MLJ 194 (refd)

Lai Kim Hon & Ors v. PP [1981] 1 MLJ 84 (refd)

Law Kiat Lang v. PP [1966] 1 MLJ 215 (refd)

Madam Guru & Anor v. Emperor [1923] Vol 24 Cr LJ 723 (refd)

Mathew Lim v. Game Warden, Pahang [1960] MLJ 89 (refd)

Mohd Ali Burut & Ors v. PP [1995] 2 AC 579 (refd)

Ng Kok Lian & Anor v. PP [1983] 2 CLJ 247; [1983] CLJ (Rep) 293 FC (refd)

Pie Chin v. PP [1985] 1 MLJ 234 (refd)

Powell and Wife v. Streatham Manor Nursing Home [1935] AC 243 (refd)

PP v. Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim (No 3) [1999] 2 CLJ 215 HC (refd)

PP v. Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim & Anor [2001] 3 CLJ 313 HC (refd)

PP v. Law Say Seck & Ors [1971] 1 MLJ 199 (refd)

PP v. Loo Choon Fatt [1976] 2 MLJ 256 (refd)

PP v. Mohamed Ali [1962] MLJ 257 (refd)

PP v. Mohd Ali Abang & Ors [1994] 2 MLJ 12 (refd)

PP v. Munusamy [1980] 2 MLJ 133 (refd)

PP v. Somwang Phattanaseng [1992] 1 SLR 138 (refd)

R v. Richard Beynon [1999] EWCA Crim 1172 (refd)

Sattar Buxoo & Anor v. The Queen [1988] 1 WLR 820 (refd)

Severo Dossi 13 Cr App R 158 (refd)

Sharom Ahmad v. PP [2000] 3 SLR 565 (refd)

Sia Soon Son v. PP [1966] 1 MLJ 116 (refd)

Sri KelangKota – Rakan Engineering JV Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Arab Malaysian Prima Realty Sdn Bhd & Ors [2003] 3 CLJ 349 FC (refd)

Tan Ewe Huat v. PP [2004] 1 CLJ 521 FC (refd)

Teoh Hoe Chye v. PP [1987] 1 CLJ 471; [1987] CLJ (Rep) 386 SC (refd)

Wong KamMing v. R [1979] 1 All ER 939 (refd)

Yap Ee Kong & Anor v. PP [1981] 1 MLJ 144 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, ss. 50(3), 87(3)

Criminal Procedure Code, s. 153(1)

Dangerous Drugs Act 1952, s. 37A(1)(a)

Evidence Act 1950, ss. 24, 114(b), 133

Penal Code, ss. 109, 377B

Counsel:

For the 1st appellant Christopher Fernando (Karpal Singh, Gurbachan Singh, Pawancheek Marican, Zainur Zakaria, Kamar Ainiah, SN Nair, Zulkifli Noordin, Marisa Regina & Saiful Idzham Ramli); Ms Karpal Singh & Co, M/s Raja Aziz Addruse, M/s Aris Rizal Christopher Fernando & Co, M/s Bachan & Kartar, M/s Merican Hamzah & Shaik, M/s Hj Sulaiman Abdullah, M/s SN Nair & Partners & M/s Zulkifli Nordin & Assoc

For the 2nd appellant Jagdeep Singh Deo (Gobind Singh Deo, Ramkarpal Singh Deo & Shamsul Iskandar Mohd Amin); M/s Karpal Singh & Co

For the prosecution Abdul Gani Patail (Mohd Yusof Zainal Abiden, Azahar Mohamed, Abdul Majid Hamzah, Mohamad Hanafiah Zakaria, Shamsul Sulaiman, Ishak Mohd Yusof, Md Azar Irwan Mohd Arifin & Ahmad Fairuz Zainol Abidin)

Case History:

Court Of Appeal : [2004] 1 CLJ 592

Court Of Appeal : [2003] 4 CLJ 409

High Court : [2000] 3 CLJ 271

JUDGMENT

Abdul Hamid Mohamad FCJ:

In this judgment, Dato’ Seri Anwar bin Ibrahim will be referred to as “the first appellant ” and Sukma Darmawan Sasmitaat Madja will be referred to as “the second appellant “.

The first appellant was charged with an offence punishable under s. 377B of the Penal Code.

The second appellant was charged with two offences. The first charge is for abetting the first appellant in the commission of the offence with which the first appellant was charged. The second charge is similar to the charge against the first appellant ie, under s. 377B of the Penal Code.

Both the appellants were tried jointly. The first appellant was convicted and sentenced to nine years imprisonment commencing from the expiry of the sentence he was then serving in the first trial (High Court Kuala Lumpur Criminal Trial No. 45481998 [1999] 2 CLJ 215 (HC), [2000] 2 CLJ 695 (CA) and [2002] 3 CLJ 457 (FC)). The second appellant was convicted on both charges and sentenced to six years imprisonment and two strokes for each charge with the sentences of imprisonment to run concurrently. For the judgment of the High Court in the present case, see [2001] 3 CLJ 313.

They appealed to the Court of Appeal. Their appeals were dismissed – see [2003] 4 CLJ 409.

They appealed to this court and this is the majority judgment of this court.

Section 87(3) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 ( “CJA 1964 “) provides that a criminal appeal to this court “may lie on a question of fact or a question of law or on a question of mixed fact and law. ” The position is the same as in the case of the Court of Appeal hearing an appeal from a trial in the High Court as in this case – see s. 50(3) CJA 1964.

In this judgment, we shall first consider whether the trial judge had correctly, in law and on the facts, called for the defence. If he had not, it would not be necessary for us to consider the defence: the appellants are entitled to an acquittal. Only, if we find that the learned trial judge had correctly called for the defence that we will have to consider whether he had correctly convicted the appellants at the close of the case for the defence.

In so doing, this court (and the trial court too), as a court of law, is only concerned with the narrow ‘legal issue ie, whether, at the end of the prosecution’s case, the prosecution had proved beyond reasonable doubt that, in respect of both appellants, the appellants had sodomised Azizan bin Abu Bakar ( “Azizan “) at Tivoli Villa one night between the month of January until March 1993 and, in respect of the second appellant only, whether he had abetted the offence committed by the first appellant.

In considering whether the defence was correctly called, this court, being an appellate court not only will consider whether all the ingredients of the offences have been proved beyond reasonable doubt, but will also consider whether there have been misdirections or nondirections amounting to misdirections that have caused a substantive miscarriage of justice.

It must be borne in mind that the duty on the part of the prosecution at the close of the case for the prosecution is to prove beyond reasonable doubt, not only, that the offence was committed one night at Tivoli Villa, but also that that “one night ” was in the month of January until and including the month of March 1993. Even if it is proved that the incident did happen but if it is not proved “when “, in law, that is not sufficient. This is because the period during which the offence is alleged to have been committed is an essential part of the charge. It becomes even more important when the defence, as in this case, is that of alibi. The appellants must know when (usually it means the day or date, but in this case the period from and including the month of January until and including the month of March 1993) they are alleged to have committed the offence to enable them to put up the defence of alibi.

In this respect we propose to take the bull by the horns. We shall consider, first, whether the prosecution had proved beyond reasonable doubt not only that the offence was committed, but whether it was committed one night during the three months’ period. That would call for the evaluation of Azizan’s evidence, and determining whether the second appellant’s confession is admissible. There will be subissues that will have to be determined eg, the impeachment proceeding against Azizan, whether Azizan is an accomplice and the issue of voluntariness of the second appellant’s confession. After deciding on those issues, we shall consider whether, in view of our findings on them, the decision of the learned trial judge to call for defence can stand. If it cannot stand, the matter ends there. If it can still stand, then only we shall consider the other issues raised at the close of the case for the prosecution. Only if after considering all the issues raised in respect of the case for the prosecution we are satisfied that the learned trial judge had correctly called for the defence that we shall consider the defence. Otherwise we do not have to as the appellants would also be entitled to an acquittal at the close of the case for the prosecution.

Credibility Of Azizan: General Observation

For reasons best known to the defence which is also not difficult for us to understand, learned counsel for the appellants, especially Mr. Christopher Fernando, kept stressing that Azizan was an outright liar. Actually, in doing so, he had placed a very high burden on the appellants. For the purpose of the case, in a criminal trial, it is not necessary for the defence to show or for the court to arrive at a conclusion that Azizan is a liar before his evidence may be regarded as unreliable. Azizan may not be a liar but his evidence may or may not be reliable. Further, some parts on his evidence may be reliable and some may not be.

Before considering Azizan’s credibility as a witness, one point must be made so that whatever conclusion we arrive at will not be an issue visavis the earlier finding of the High Court in the first trial which had been confirmed by the Court of Appeal and this court.

It is to be noted that Azizan’s credibility had been considered in the earlier case. All the three courts, including this court, had found that he was a credible witness.

We must point out that that is a separate matter. His credibility as found by the courts in that case was in respect of that case, based on the evidence he gave in that case. In that case the main issue was whether the first appellant directed Dato’ Mohd. Said bin Awang, Director of the Special Branch and Amir Junus, Deputy Director II of the Special Branch to obtain a written statement from Azizan denying and withdrawing his (Azizan’s) allegation of sodomy against the first appellant as contained in his (Azizan’s) statutory declaration dated 5 August 1997 (exh. P14C in the first trial and exh. P5 in this trial which will be referred to as exh. P14C/P5) which they (Mohd. Said and Amir Junus) obtained in the form of a written statement dated 18 August 1997 (exh. P17 in the first trial). That was the substance of the offence in the first trial. The substance of the main offence in the instant appeal is whether the appellants sodomised Azizan at Tivoli Villa one night in January until and including March 1993.

Secondly, is it true that Azizan’s statutory declaration dated 5 August 1997 (exh. P14C/P5) and Azizan’s statement dated 18 August 1997 (exh.P17 in the earlier trial) featured strongly in this trial and appeal. But, as pointed out by this court, in the judgment of Haidar FCJ (as he then was) in the earlier appeal at p. 476:

In respect of (1) (ie, allegation of sodomy by the first appellant in Exh. P14C/P5 – added), after the evaluation of the evidence, the learned judge ruled there is evidence to show that Ummi and Azizan had made the allegations. In fact, in our view, the defence did not seriously dispute that the allegations were made but contended that they were false and fabricated. However, in view of the amendment to the charges, the truth or falsity of the allegation was no longer in issue. There are no reasons for us to disagree with the learned judge when he said at p. 333 that:

… there is evidence to show that Ummi and Azizan had made the allegations against the accused.

The principles adopted by the appellate courts not only in this country but also in other common law jurisdictions have been reproduced at length by the Court of Appeal – see from pp. 450 to 452 of [2003] 4 CLJ 409. The Court of Appeal reproduced dicta made in the following cases: Clarke Edinburgh Tramways [1919] SC (HL) 35 at p. 36 (per Lord Shaw of Dunfermline), Powell and Wife v. Streatham Manor Nursing Home [1935] AC 243 at p.249 (per Viscount Sankey LC), Herchun Singh & Ors. v Public Prosecutor [1969] 2 MLJ 209 at p. 211 (per HT Ong CJ (Malaya), Lai Kim Hon & Ors v. Public Prosecutor [1981] 1 MLJ 84 (per Abdul Hamid FJ (as he then was), Kandasamy v. Mohamed Mustafa [1983] 2 MLJ 85 (PC) (per Lord Brightman) and Goh Leng Kwang v. Teng Swee Lin & Ors [1994] 2 MLJ 5 (Singapore). Even learned counsel for the appellants did not disagree with the principles stated in those cases. We shall not repeat them except to quote a few short passages from the judgments and point out the contexts in which they were made.

In Herchun Singh & Ors v. Public Prosecutor [1969] 2 MLJ 209 at p. 211, HT Ong (CJ (Malaya)) said:

This view of the trial judge as to the credibility of a witness must be given proper weight and consideration. An appellate court should be slow in disturbing such finding of fact arrived at by the judges, who had the advantage of seeing and hearing the witness, unless there are substantial and compelling reasons for disagreeing with the finding: see Sheo Swarup v. KingEmperor AIR [1934] PC 227.

It must be noted that, in Herchun Singh ‘s case (supra), the police report made shortly after the robbery by the complainant, not only failed to identify the appellants but contained a further statement “I do not know them (saya tidak kenal) “. This was contradicted by the complainant who denied those words, in fact, he remembered telling the police about Adaikan, the third appellant, as well as giving a description of the first appellant. He remembered telling the policeman who wrote the complainant’s police report that there were Sikhs among the robbers and that one of them was a brother of the estate watchman but whose name he could not recollect at the time he made the report. Ong Hock Thye (CJ (Malaya)) then said:

The learned trial judge, having heard the complainant’s explanation, was satisfied that the latter was still very much shaken by the alarming experience he had undergone when he made his report but that, despite his agitation, he did mention the names to the police. This was a finding of fact that the report which was taken down contain errors and omissions for which the constable was responsible.

This passage is then followed by the passage quoted earlier. So, that passage must be read and understood in the light of that finding of fact ie, that the police report contain errors and ommissions. Indeed, in Herchun Singh ‘s case (supra) the learned Chief Justice (Malaya) distinguished Ah Mee v. Public Prosecutor [1967] MLJ 220 (FC). In that case, a rape case, the Federal Court held that in view of the inconsistencies in the evidence of the complainant it was unsafe to rely on her uncorroborated evidence and therefore the conviction must be set aside. This is in spite of the fact that the trial judge considered that the complainant’s credibility was unimpeached and had stated that he was personally impressed by his demeanor.

Ah Mee (supra) is a case where the complainant’s own evidence is inconsistent, not a case in which the evidence of one witness on a particular point is contradictory to that of another witness, and the judge believes one witness and not the other.

We shall only refer to another Federal Court judgment in Lai Kim Hon & Ors v. Public Prosecutor [1981] 1 MLJ 84. In that case, in a passage quoted by the Court of Appeal in the instant appeal, Abdul Hamid FJ (as he then was) said:

Viewed as a whole it seems clear that the finding of fact made by the trial judge turned solely on the credibility of the witnesses. The trial judge heard the testimony of each witness and had seen him. He also had the opportunity to observe the demeanour of the witnesses. Discrepancies will always be found in the evidence of a witness but what a judge has to determine is whether they are minor or material discrepancies. And which evidence is to be believed or disbelieved is again a matter to be determined by the trial judge based on the credibility of each witness. In the final analysis it is for the trial judge to determine which part of the evidence of a witness he is to accept and which to reject. Viewed in that light we did not consider it proper for this court to substitute its findings for that of the learned trial judge.

The principle of law governing appeals in criminal cases on questions of fact is well established, in that the Appeal Court will not interfere unless the balance of evidence is grossly against the conviction especially upon a finding of a specific fact involving the evaluation of the evidence of a witness founded on the credibility of such witness.

In that case the Federal Court did not interfere with the finding of the trial judge because the court was of the view that the trial judge had enough evidence before him which, if believed, would justify his finding the appellant guilty.

Of course, the general principle is not in dispute. However, it is the application of the principle to a particular situation that is difficult and, more often then not, in dispute.

Clearly, an appellate court does not and should not put a brake and not going any further the moment it sees that the trial judge says that that is his finding of facts. It should go further and examine the evidence and the circumstances under which that finding is made to see whether, to borrow the words of HT Ong (CJ Malaya) in Herchun Singh ‘s case(supra) “there are substantial and compelling reasons for disagreeing with the finding. ” Otherwise, no judgment would ever be reversed on question of fact and the provision of s. 87 CJA 1964 that an appeal may lie not only on a question of law but also on a question of fact or on a question of mixed fact and law would be meaningless.

Azizan’s credibility was attacked, first, through the impeachment proceeding and, having failed in the impeachment proceeding, on ground of contradictions in his evidence made in the earlier trial and in this trial. The learned trial judge correctly stated in his judgment that the “defence is entitled to embark on the assault of the credibility of Azizan based on the facts of the case even after a ruling has been made by the court that his credit is saved. ” – see p. 367, letter “b ” of [2001] 3 CLJ 313. The Court of Appeal, after citing the learned trial judge at length and stating the law, agreed with the decision of the learned trial judge on the impeachment proceeding and the learned trial judge’s finding that “Azizan was a reliable, credible and truthful witness notwithstanding some of the discrepancies and contradictions that were highlighted by the defence. ” – see p. 460, letter “d ” [2003] 4 CLJ 409.

It is said that these are concurrent finding of facts of the two courts but, again, that does not mean that this court should shy away from analysing the evidence to see whether there are “substantial and compelling reasons for disagreeing with the finding “, again borrowing the words of HT Ong (CJ (Malaya) in Herchun Singh (supra).

Impeachment Proceeding

The impeachment proceeding was in respect of Azizan’s inconsistent statements in his testimony in the previous trial and in this trial. The inconsistent statements are, in brief, in the first trial he said he was not sodomised by the first appellant after May 1992. But in this trial, he said that he continued to be sodomised after that. This becomes of utmost importance because the charge, as finally amended, gives the date of the offence as from January until March 1993. His explanation was that what he meant by the earlier statement was that he was not sodomised in the first appellant’s house after May 1992.

The learned trial judge accepted Azizan’s explanation that what he meant by the statement that he was not sodomised by the first appellant after September (later, May) 1992 was that he was not sodomised in the first appellant’s house. His reason was that the questions were asked in relation to his visits to the first appellant’s house after May 1992. The Court of Appeal found that there was nothing wrong with the conclusion of the learned trial judge. Even though we are not absolutely satisfied with the explanation, we are not inclined to disturb that finding for the following reasons. First, unlike the learned trial judge, we do not have the advantage of seeing and hearing the witness.

Secondly, in an impeachment proceeding, Azizan was placed in the position of an accused. Therefore, if there is any doubt, the benefit of the doubt should be given to him.

Thirdly, the effect of impeachment seems to be very harsh. Not only his whole evidence will be disregarded, he is also liable to prosecution for perjury. On the question whether, where a witness is impeached, his whole evidence is to be disregarded, there appears to be conflicting decisions in our courts. Earlier cases seem to take the rigid view that once a witness is impeached, his whole evidence becomes worthless (see Koay Chooi v. R. [1955] MLJ 209, Mathew Lim v. Game Warden, Pahang [1960] MLJ 89 and Public Prosecutor v. Munusamy [1980] 2 MLJ 133 (FC). On the other hand, in Public Prosecutor v. Mohd. Ali bin Abang & Ors. [1994] 2 MLJ 12, Chong Siew Fai J (as he then was) took the view that the fact that the credibility of a witness is impeached does not mean that all his evidence must be disregarded. It is still incumbent upon the court to carefully scrutinize the whole of the evidence to determine which parts of her evidence are the truth and which should be disregarded. The learned judge followed the Singapore case of Public Prosecutor v. Somwang Phattanasaeng [1992] 1 SLR 138. Indeed there is also another Singapore High Court case to the same effect: Public Prosecutor v. Mohammed Faizal Shah [1998] 1 SLR 333. However, no reference was made to the earlier Malaysian cases, including the judgment of this court in Munusamy (supra).

As the point was not argued before us, and also since it is not necessary for this court to decide on the issue in this appeal, we would leave it to another occasion and in a proper case for it to be decided upon by this court, if it need be.

The point is, if we accept the view prior to Mohd. Ali bin Abang (supra), which we should, in view of Munusamy (supra), a Federal Court judgment, then the effect of an impeachment order, if made against Azizan would be very drastic. Not only that, he may even be subject to prosecution.

But, the fact that he was not impeached does not mean that his whole evidence must be believed. His evidence will have to be scrutinised with care, bearing in mind the dent in his credibility caused by his contradicting statements. At the end of the day, his evidence may be found to be reliable in some parts and not in others. And, at that stage, if there is any doubt, the benefit of the doubt must be given to the appellants because they are the accused.

Azizan’s Evidence Regarding The Date Of Offence

The only person who was present during the alleged incident, other than the appellants, was Azizan. The person who was alleged to have been sodomised was Azizan. So, he should be the only person, other than the appellants, who should know when he was sodomised.

Is he really consistent in his evidence about the “date ” of the offence?

The first time he mentioned about the date of sodomy (at luxurious hotels), was in Exh. P14C/P5 dated 5 August 1997. The period given was around 1992 ( “sekitar tahun 1992 “). But, in P14C/P5 he did not mention Tivoli Villa. So we do not know whether he meant to include it or not. In any event, in the charge dated 5 October 1998 against the first appellant regarding Tivoli Villa incident, the date of the commission of the offence was stated as “May 1994 ” (Jilid 1, p. 239).

Who gave the “May 1994 ” date to the police? Logically, the date of the commission of the offence could only come from Azizan as he was the “victim “, the only person present other than the appellants.

In this trial, on 3 August 1999, Azizan was crossexamined by Mr. Christopher Fernando:

S: Adakah kamu beritahu pihak polis kamu diliwat pada bulan Mei 1994?

J: Saya tak ingat.

…

S: Adakah kamu tahu tuduhan asal terhadap Dato’ Seri Anwar adalah pada Mei 1994?

J: Ya, saya tahu.

S: Adakah kamu diberitahu polis kamu diliwat pada bulan Mei 1994?

J: Saya tak ingat.

(Jilid 2, p. 992 to 993)

On 4 August 1999, still under crossexamination:

S: Adakah awak beritahu polis bahawa awak diliwat oleh Dato’ Seri Anwar dan Sukma pada bulan Mei 1994?

J: Tidak.

(Jilid 2, p. 999)

Still under crossexamination on 9 August 1999:

S: Adakah tidak sebelum hari ini awak ada memberitahu mahkamah ini bahawa awak tidak ada memberitahu polis bahawa awak diliwat oleh Dato’ Seri Anwar dan Sukma pada tahun 1994?

J: Ada.

S: Jikalau awak tidak beritahu tarikh iaitu tahun 1994 siapakah beritahu polis ianya berlaku dalam bulan Mei 1994? (Tidak ada jawapan).

(Jilid 2 p. 1028 to 1029)

On 16 August 1999, now under reexamination by the Attorney General:

S: Adakah awak katakan apaapa kepada polis mengenai apaapa kejadian dalam tahun 1994.

J: Saya beritahu polis yang saya ada diliwat pada tahun 1994.

(Jilid 2, 1055)

So, having denied that he informed the police that he was sodomised by the appellants in 1994, he finally admitted that he did tell the police that he was sodomised in 1994. That answers the question that he earlier on did not answer when asked: if he did not tell the police the 1994 date who informed the police that the incident happened in May 1994?

On 23 April 1999, the second appellant was charged. The date of the offence was given as “May 1992 “. Three days later, on 27 April 1999, the charge against the first appellant was also amended from “May 1994 ” to “May 1992 “. How did this date come about? SAC1 Musa provides the answer: it was based on “other statements ” made by Azizan. (Jilid 2. Page 1101). After the amendment, notices of alibi were served on the prosecution. Then, it was found that the construction of Tivoli Villa had not been completed yet!

On this point, the evidence of Azizan given on 4 August 1999 reads:

S: Setuju atau tidak pada bulan Mei 1992, Tivoli Villa (belum siap dibina)?

J: Setuju.

(Jilid 2, page 998).

On 7 June 1999 the charges were amended from “May 1992 ” to “between the month of January until March 1993 “.

On 3 August 1999 under crossexamination, Azizan said that he gave that “date ” to the police on 1 June 1999 (Jilid 2, p. 993).

Towards the end of his evidence, when reexamined by the then Attorney General, another point cropped up. Azizan said:

J: SAC1 Musa telah meminta saya untuk mengingati dengan jelas tentang kejadian pertama kali saya diliwat di Tivoli Villa. (emphasis added)

(Jilid 2, page 1064)

Note that he now talked about SAC1 Musa asking him to remember the incident that he was sodomised by the appellants for the first time at Tivoli Villa. SAC1 Musa (SP9) also said the same thing:

J: Saya minta Azizan mengingatkan tarikh pertama kali dia di liwat oleh Dato’ Seri Anwar dan Sukma di Tivoli Villa. (emphasis added).

(Jilid 2, page 1096)

So, even at the end of his evidence, while he was certain about the January until March 1993 date, he came up with another poser: was there a second or third incident that he was sodomised by both the appellants at Tivoli Villa?

To sum up, he gave three different dates in three different years, the first two covering a period of one month each and the third covering a period of three months as the date of the alleged incident.

Regarding his finding on Azizan’s credibility, the learned trial judge said:

It is to be observed that May 1994 and May 1992 are not the months we are concerned with in the instant charges against both the accused. These months are relevant only in respect of the earlier charges which have been amended. We are not concerned with these charges. I had dealt with the amendment of these charges earlier in this judgment and had ruled that the amendment was lawfully made in the proper exercise of the discretion by the Attorney General. In his testimony Azizan said he was confused because he was asked about the months of May 1994 and May 1992 repeatedly as stated above. I find as a fact that he was confused. When a witness is confused, it does not mean he was lying. The naked truth is that he could not remember what he had said. I am satisfied he was not lying. In any event, the issue whether he told the police he was sodomized in May 1994 and May 1992 are not the issues in the current charges against both the accused. The issue is whether he was sodomized by both the accused between the months of January and March 1993 at Tivoli Villa. I therefore rule the credit of Azizan is not affected on this score.

It was also argued that the evidence of Azizan cannot be accepted in the light of the evidence of SAC1 Musa. It was pointed out that SAC1 Musa in his evidence said five statements were recorded from Azizan and that all these statements were in relation to sodomy. The allegations are consistent and true. He also testified that there was a necessity to amend the charges because there were contradictions in the date. It was submitted that there were two versions of the prosecution case on a fundamental ingredient ie, the dates. In this respect, it is necessary to recapitulate what Azizan had said about the dates. In his evidence which I had referred to earlier he was confused about the dates as he was asked repeatedly the same questions on the dates May 1994 and May 1992. In substance what he said on this issue was that he could not remember whether he told the police he was sodomized in May 1994 although he did say that he did not inform the police that he was sodomized in 1992.

Be that as it may, the evidence of SAC1 Musa clearly states that Azizan was consistent in his statements on the issue of sodomy although he was not sure of the exact dates. The relevant dates we are concerned with in the present charges are between the months of January and March 1993. Azizan emphatically said in evidence that he was sodomized by both Dato’ Seri Anwar and Sukma at Tivoli Villa between January to March 1993. Whether he was sodomized in May 1994 or May 1992 is not relevant as these dates are not in issue to be decided in this case. I see no merits on this contention and the credit of Azizan is not affected on this ground. (Page 371 to 372 of [2001] 3 CLJ 313 ).

It is true that May 1994 and May 1992 are not the dates that we are concerned with in the instant charges. But, in determining whether Azizan’s evidence regarding the date in the present charges is reliable or not we do not think that they are not relevant. All the dates must have been given by Azizan as he was the “victim ” and the only person present during the incident other than the appellants. Indeed evidence shows that he did give those dates to the police. We accept that he may not be lying. He may be confused. May be he cannot remember because the incident happened many years earlier and unlike in most sexual cases, he did not lodge a police report immediately. In fact he did not lodge a police report at all. But, the fact that he may be confused or he cannot remember is the point. You do not prove a thing by forgetting or by being confused about it. That is why the charge against the first appellant had to be amended twice. The fact that the amendments were lawfully made is of no consequence. We accept that the amendments were lawfully made. But, we are talking about the consistency of Azizan’s evidence regarding the date of the commission of the offence.

And, it is not a matter of one or two days, one or two weeks or even one or two months. It covers a period of three years (1992, 1993 and 1994) and, even the last date given was one night in a period of three months!

Furthermore, we note that on the issue whether he informed the police that he was sodomised in 1994, having said he could not remember twice, Azizan denied informing the police, but under reexamination he admitted that he did inform the police of the fact. We also note that the learned trial judge had recorded his observation of Azizan when giving evidence, eg, “tidak ada jawapan “, “witness is very evasive and appears to me not to answer simple question put to him. ”

In the circumstances, even though, for the reasons that we have given, we do not interfere with the finding of the trial judge in the impeachment proceeding, when we consider Azizan’s evidence as a whole, we are unable to agree with the “firm finding ” of the learned trial judge and the Court of Appeal that Azizan “is a wholly reliable, credible and truthful witness “. Evidence does not support such a finding. He was most uncertain, in particular about the “date ” of the offence, not just the day or the week or even the months but the year. We do not say he is an “outright liar ” as Mr. Christopher Fernando was trying to convince us. But, considering the whole of his evidence, he is certainly not the kind of witness described by the learned trial judge.

Is Azizan An Accomplice?

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal found that Azizan was not an accomplice. On this point too we are not going to repeat the law which has been stated by both the High Court and the Court of Appeal. Instead, we will focus on the facts.

The reason for his finding that Azizan was not an accomplice is to be found in this paragraph.

In the instant case the evidence shows that Azizan was invited to visit Tivoli Villa by Sukma. Azizan went there to see Sukma’s new apartment. He went there not with the intention of committing sodomy with both the accused. His actus reus alone is not sufficient to make him an accomplice, there must also be the intention on his part (see Ng Kok Lian ‘s case). For reasons I therefore find that Azizan is not an accomplice. (p. 366 of [2001] 3 CLJ 313.

The Court of Appeal added nothing to it in agreeing with the finding of the learned trial judge.

In our view, if the learned trial judge was looking for mens rea he should look at the surrounding circumstances. This is where evidence of similar facts becomes relevant. This is not a case of a person who was merely present at the time of the commission of the offence or participated in it only once. By his own evidence, he was sodomised 10 to 15 times at various places, including in the house of the first appellant over a number of years. He never lodged any police report. He never complained about it until he met Ummi in 1997. He did not leave the job immediately after he was sodomised the first time, we do not know when. Even after he left the job, he went back again to work for the first appellant’s wife. Even after he left the second time, he continued to visit the appellant’s house. He even went to the first appellant’s office. When invited by the second appellant to go to Tivoli Villa, he went. He said he was surprised to see the first appellant there. Yet he stayed on. Signalled to go into the bedroom, he went in. There is no evidence of any protest. He followed whatever “instructions ” given to him.

He said he submitted under fear and was scared of both the appellants. A person may allow himself to be sodomised under fear once or twice but certainly not 10 to 15 times over a number of years. He is not a child nor an infirm. Even on this occasion, when he saw the first appellant there, he would have known of the possibility of the first appellant wanting to sodomise him again. Why did he not just go away? Instead, by a mere signal, he went into the bedroom, as if he knew what was expected of him. He did nothing to resist, in fact cooperated in the act. And, after the first appellant had finished and went to the bathroom, he remained in that “menungging ” position. What was he waiting for in that position? Indeed the whole episode, by his own account, appears like a repetition of a familiar act in which each actor knows his part. And, after that he went back to the place again, twice and talked about the incident as “the first time ” he was sodomised there, giving the impression that there was a second or third time. Are all these consistent with a person who had submitted under fear? We do not think so. Therefore, in our judgment Azizan is an accomplice, though he may be a reluctant one.

Second Appellant’s Confession

The prosecution sought to introduce the confession of the second appellant recorded by Encik Abdul Karim bin Abdul Jalil, a Session’s Court Judge acting as a Magistrate ( “the magistrate “) on 17 September 1998.

A trial within a trial was held. At the end of it the learned trial judge held that the confession was properly recorded and voluntarily made and admitted it as evidence. The Court of Appeal agreed with him.

The attack on the confession can be divided into two parts. The first was on what the magistrate did or did not do in recording the confession. This has been enumerated by the learned trial judge as points (a) to (g) – see p. 345 of [2001] 3 CLJ 313. We have no reason to differ from the findings of the learned trial judge on those points.

The second part is on the issue of voluntariness of the confession. In this regard, the fact the magistrate who recorded the confession said that he was satisfied that the confession was made voluntarily, does not mean that the trial court must accept that the confession was voluntarily made. The magistrate formed his opinion from his examination, oral and physical, and his observation of the confessor. He formed his opinion from what he saw of the confessor and what was told to him by the confessor, in answer to his questions or otherwise. A confessor may, at the time of making the confession, tell a magistrate that he is making the confession voluntarily and the magistrate may believe him. But, that does not mean that the trial court must automatically accept that the confession was voluntarily made and therefore admissible. If that is the law, then the trial within a trial would not be necessary at all because every confession that is recorded by a magistrate is recorded after the magistrate is satisfied of its voluntariness. But, though the magistrate may be justified based on his examination and observation of the confessor that the confessor was making the confession voluntarily, the trial court, after holding a trial within a trial and hearing other witnesses as well, may find otherwise. That is what a trial within a trial is for.

We do not question the opinion of the learned magistrate that he was satisfied that the second appellant was making his confession voluntarily. Neither do we find that the other grounds forwarded in respect of the recording of the confession have any merit.

What is more important is for this court to examine whether the finding of the learned trial judge that the confession was voluntarily made after the trial within a trial is correct.

In this regard too, the learned trial judge had stated the law correctly which was amplified by the Court of Appeal (see p. 474477 of [2003] 4 CLJ 409). We agree with them. However, we would like to add that, of late, this court, in considering the voluntariness of cautioned statement made under s. 37A of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 has accepted that if there appears to be “suspicious circumstances surrounding the making of, or recording of, the cautioned statement ” it is incumbent on the trial judge to hold it inadmissible:Tan Ewe Huat v. Public Prosecutor [2004] 1 CLJ 521 FC. In so doing, this court followed the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Chan Ming Cheng v. Public Prosecutor [2002] 4 CLJ 77 in which Gopal Sri Ram JCA, delivering the judgment of the court said:

There is no burden on an accused person to prove that the statement recorded from him is involuntary. The burden lies on the prosecution to show positively that the statement was voluntarily given. There is also no burden on an accused to raise a reasonable doubt as to the voluntariness of a cautioned statement. The only burden on an accused is to show suspicious circumstances surrounding the making of or recording of the cautioned statement. So long as the suspicion is reasonable as to the voluntariness of the statement, it is incumbent on the trial judge to hold it inadmissible.

It must be pointed out that the provision of s. 37A(1)(a) of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 is similar to the provision of s. 24 of the Evidence Act 1950.

In dealing with this issue, it appears to us that the learned trial judge considered each allegation by the second appellant and denial by the police officers in question and concluded that he believed the police officers and held that the confession was voluntarily made.

In the circumstances of this case which, we must say, is different from any other case that we know of, we think we have to consider the whole circumstances surrounding the arrest of the second appellant and the related investigations.

As we are considering the question of voluntariness of the confession which is a question of fact, we have no choice but to reproduce the evidence, even though it is quite long.

We shall summarise the evidence of the second appellant first. The second appellant was arrested by ASP Rodwan (TPW3) and three other police officers at about 1pm on 6 September 1998 at Societe Cafe, Lot 10 Shopping Complex, Bukit Bintang. He was then having lunch with his sister Komalawati (TDW2). He was taken to the lower ground of Lot 10 and pushed into a Proton Saga car and his hands were handcuffed. He was then taken to his car. ASP Rodwan and the other police officers ransacked ( “membongkar “) his car in the presence of the public. From there he was taken to Bukit Aman. During the journey, ASP Rodwan played the speech of the first appellant condemning ( “memaki dan mencaci “) the former Prime Minister.

They stopped at Bukit Aman only to park the second appellant’s car and then proceeded to his apartment at Tivoli Villa. In the car he was verbally abused ( “memaki hamun “). At the apartment they ransacked the whole place but did not find anything that they were looking for. They broke the door of the room of the second appellant’s sister in spite of the fact that he told them that the key was with her. Between 3pm to 4pm he was taken to Bukit Aman. At ASP Rodwan’s office he was asked to sit at one corner with his hands handcuffed. At that time, they were jumping merrily ( “bersukasuka dan meloncatloncat “). ASP Rodwan was filling a form. At that time the second appellant heard Zaini, one of the officers, asking ASP Rodwan: “Boss, borang nak tahan dia ni atas dasar apa? Rodwan jawab “entah. ” He was taken to the lock up. Before entering he was asked to remove all his clothes except for his under pants. He was not given food that evening/night as he was told by the officer in charge of the lockup that meal time was over. In fact he had not eaten the whole day.

On the second day, in the morning, 7 September 1998, he was taken to ASP Rodwan’s offfice. There he met a person by the name of “Zul ” (ASP Zulkifly bin Mohamed, TPW4). After ascertaining his identity, according to the second appellant, ASP Zulkifli lifted his shirt and pinched his nipple while making fun of him using shameful words ( “memulasmulas buah dada (nipple) saya dengan sekuatkuatnya dengan mempersendakan diri saya dengan katakata yang memalukan “). At the office, ASP Rodwan asked him to make a statement regarding his homosexual relationship with the first appellant. When he denied, ASP Rodwan challenged him to take an oath with the Quran in the presence of a religious teacher ( “Ustaz “). He accepted the challlenge but no “Ustaz ” came.

Later in the same day, 7 September 1998, he was taken to see a magistrate. The magistrate made a remand order of two weeks straight away.

In the afternoon, he was taken back to Bukit Aman. There ASP Rodwan told him that he was under his (ASP Rodwan’s) detention ( “di bawah tahanan saya “) and it was better for him to tell about his (the second appellant’s) homosexual relationship with the first appellant. When he denied, ASP Rodwan told him if he was prepared to talk he could go home faster. If not he would be handed over to the Special Investigation Unit which officers were very rough and he would regret later.

He also said he was suffering from asthma and at night it became worse and he asked to be allowed to wear his Tshirt to cover his chest.

At about 7am on the third day, 8 September 1998, two officers took him to a meeting room at the third floor. There were six officers in the room. In the room he was asked to strip naked, while still being handcuffed and he was asked to turn around so that they could see his whole body. When he sat down on a chair, all the officers simultaneously scolded him: “Who ask you to sit down? ” They removed his spectacles and knocked it ( “mengetukngetuk “) as if to break it. After he sat down an officer stood up, kicked his chair and he fell down. They did not question him then.

They merely scolded him simultaneously and continuously very close to his ears in a very high and rough tone. This went on until about 1.30pm. He was in that room from about 8am or 8.30am to about 1.30pm.

After lunch, at about 2pm or 2.30pm he was taken to the same room again. The same thing happened again, until about 4.30pm or 5pm.

On the fourth day, 9 September 1998, he was taken to a room. There were a few people there including one Dr. Zahari (Dr. Zahari Noor (TDW5)). Dr. Zahari examined his whole body paying particular attention to his private part and his anus. He also inserted his finger into his (the second appellants’) anus. He was naked during the examination. ASP Rodwan directed the cameraman to take photographs of the second appellant while naked but Dr. Zahari stopped it as he did not require the photographs. But ASP Rodwan said it was necessary for the purpose of the investigation. Photographs of him, naked and in various positions and close ups of his private part, were taken (and in fact tendered in the main trial as P7 AG.)

After that he was taken to the same room on the third floor again. There were six people there. The second appellant identified C/I Sampornak bin Ismail (TRW2), D/Kpl Ahmad Bustami bin Ayob (TRW3), D/Kpl Mokhtaruddin bin Suki (TRW5), D/Kpl. Hamdani bin Othman (TRW4). They told him that the photographs would be used as evidence, but not for what.

As had happened on the previous day, he was roughly scolded until about 4.30pm or 5pm.

On the fifth day, 10 September 1998, the interrogation continued. On that day they were rougher. They threatened that if he did not follow their instructions he would be detained under the Internal Security Act for two years and then for a further two years. They also told thim that he could be charged like Dato’ Nalla. They could place bullets in his car which was then at Bukit Aman. They also threatened him that they could pay someone to shoot him and no one would suspect the police for it.

On 11 September 1998, the sixth day, his stand was not strong anymore ( “saya tidak lagi teguh dengan pendirian saya “) because he could no longer bear what was being done to him and he followed their instructions. After that they became nice to him. They removed the handcuff, lowered their voices, allowed him to wear shirt and trousers, gave him drink, cigarette and cakes in the morning. Asked by learned counsel, what they wanted from him, the second appellant said that they wanted him to admit that he had sexual relationship with the first appellant.

The interrogation continued on the following days, in a more friendly manner.

On 16 September 1998, the eleventh day of his detention, at about 7.30am or 8.30am ASP Rodwan came to see him at the lockup. He informed the second appellant that he should make a statement before a magistrate. He agreed after ASP Rodwan told him that he would be released after making a confession before a magistrate. On the following day, 17 September 1998, the twelfth day, he was taken to see the magistrate (TPW1) who recorded his confession. Asked by his counsel how he could make such a long confession, about 10 or 12 pages, he said he was guided by ASP Rodwan repeatedly. ASP Rodwan also told him it was alright if he were to make mistakes but what was more important was to give a clear and detailed evidence ( “keterangan “) about his homosexual relationship with the first appellant and Azizan.

Crossexamined by Mr. Karpal Singh he said that from 6 September 1998 to 16 September 1998 he was taken to the interrogation room every day including Sunday. Each day he was interrogated from about 8.30am to 1pm and from about 2pm or 2.15pm until 4.30pm, though at times until 5.30pm or even 6.30. It was about 8 hours a day for 10 days.

Still under crossexamination by Mr. Karpal Singh, on 18 September 1998 (one day after the confession was recorded) SAC1 Musa told him that if he engages his own lawyer he would be charged under s. 377B of the Penal Code but if he uses the lawyer appointed by him ( “jika saya gunakan yang dia lantik “) he would only be charged under s. 377D and would be sentenced to three months only. The lawyer in question is Encik Mohd. Noor Don who went to see him at about 4.30pm on the same day, 18 September 1998. He said Mohd. Noor Don told him if he pleaded guilty and said he had repented ( “bertaubat “) he would only be sentenced to one day imprisonment.

Under crossexamination by Dato’ Gani, he admitted that he had filed an affidavit in Criminal Case No.441661998 that the name of the lawyer mentioned by SAC1 Musa was Zulkifli Nordin instead of Mohd. Noor Don. He also admitted that on 30 September 1998 (note that this is 11 days after he was charged in the sessions court in which he was represented by Mohd. Noor Don) he signed a letter confirming that Mohd. Noor Don had acted for him on 19 September 1998 on his instructions. However, he said he was forced to sign the letter by SAC1 Musa. Then he was referred to Tun H.S.Lee Police Report No. 25536/98 (exh. TP1) lodged by the second appellant.

Under reexamination he explained the inconsistency between his affidavit dated 10 December 1998 while he was under detention at Bukit Aman and his evidence in court thus: Mohd. Noor Don told him that SAC1 Musa told him (Mohd. Noor Don) that he (the second appellant) would be sentenced to one day imprisonment but the second appellant told Mohd. Noor Don that SAC1 Musa had told him (the second appellant) that the sentence would be three months. Mohd. Noor Don then went to see SAC1 Musa and came back and told him (second appellant) that he (Mohd. Noor Don) had confirmed with SAC1 Musa that the sentence would be one day imprisonment.

He also confirmed that the letter dated 30 September 1998, signed by the second appellant confirming the appointment of Mohd. Noor Don as his (the second appellant’s) counsel was prepared by SAC1 Musa.

An important witness for the second appellant in the trial within a trial is Mr. Ganesan a/l Karupanan, an advocate and solicitor (TDW4). He said that he was appointed to act for the second appellant on 6 September 1998. On the next day, he came to know that the second appellant was at Bukit Aman. He wrote a letter to the Inspector General of Police. On 8 September 1998 in an attempt to meet the second appellant, he went to see ASP Rodwan at Bukit Aman.

He was told that he had to get the permission of SAC1 Musa.

On the following day, 9 September 1998 he wrote to SAC1 Musa informing him that the second appellant’s sister would like to see him. He tried to see the second appellant on 7, 8, 9 and 11 September 1998 but was not successful. He even wrote to the Attorney General seeking his assistance. On 14 September 1998 ASP Rodwan called him and told him to go to his office because he wanted to record a statement from him. He also contacted SAC1 Musa who told him the same. Neither SAC1 Musa nor ASP Rodwan contacted him before the second appellant was charged in the Session’s Court on 19 September 1998. Under crossexamination by Mr. Christopher Fernando he said he made six attempts altogether, three were purely to see the second appellant and the other three were in respect of the recording of his statement.

Under crossexamination by Mr. Karpal Singh he said that between 7 September 1998 until 18 September 1998 he was not told by the police or the Attorney General’s Chambers that some other lawyer had taken over as counsel for the second appellant. However, on 19 September 1998 the day the second appellant was charged in the Session’s Court, at 9am he received a telephone call from Mohd. Noor Don who told him that the second apellant had appointed him as his counsel. Mohd. Noor Don also told him that he received a telephone call from the second appellant the previous night who wanted him (Mohd. Noor Don) to act for him.

Regarding Zulkifli Nordin, Ganesan said he told Zulkifli to check what was happening in court on 19 September 1998.

Under crossexamination by Datuk Gani he said he was appointed to act for the second appellant by the second appellant’s sister, Komalawati.

At the beginning of the trial within a trial the prosecution called 4 witnesses. I shall skip the evidence of Encik Abdul Karim, the recording magistrate. The second witness, Mr. Kathi Velayudhan a/l Palaniappan (TPW2) merely produced the records of proceedings in Criminal Case No.6213598, which also includes the confession that was tendered in mitigation.

The third witness was ASP Mohd. Rodwan bin Hj. Mohd. Yunus (TPW3). He informed the court that he arrested the second appellant on 6 September 1998 at about 1pm at Lot 10, Bukit Bintang. On the following day, 7 September 1998, at about 12.45pm he took the second appellant to see a magistrate who made a remand order effective from 7 September 1998 to 20 September 1998 (a period of 14 days).

According to him, on 16 September 1998 at about 3pm, the second appellant was brought to his office. After the second appellant told him something he took the second appellant to see SAC1 Musa. SAC1 Musa asked him to tape the second appellant’s confession. The reason was because the case was a sensitive case and it was to avoid accusations ( “tohmahan “) that it was a police invention being made later. The recording was done from 4.30pm to 5.05pm.

On 17 September 1998, ASP Rodwan took the second appellant to see a magistrate because the second appellant “wanted to make a confession on his own will “.

Crossexamined by Mr. Govind Singh Deo, ASP Rodwan admitted that the second appellant was investigated in relation to Police Report No. 14140/98 lodged by Mohd. Azmin Ali mentioned earlier. Asked whether the second appellant was investigated as a witness, ASP Rodwan replied that he recorded the second appellant’s statement as a witness. He admitted that he did not contact the second appellant before he was arrested. He admitted that at Tivoli Villa he was told by the second appellant that the key to his sister’s room was with her and agreed that they (the police party) broke the door to the room. He admitted, at Tivolli Villa, the second appellant was handcuffed. He denied that the second appellant was made to remove all his clothes except for the under pants while at the lockup. Asked about his duties in the investigation of the case, he said it was to assist in the investigation regarding the book “50 Dalil “. The interrogation was done by “pihak Bantuan Teknik ” from the Interrogation and Photography Division of the Criminal Division (my translation). He admitted that when he took the second appellant to see the magistrate on 7 September 1998, it was he who asked for a 14day remand straight away. He also admitted it was not a normal practice for a magistrate to make a 14day remand order. When asked, he answered that he took the second appellant to see the magistrate who gave the 14day remand order at the High Court, not at the magistrate’s court, as usual. Asked why, he said it was because he was instructed (by SAC1 Musa) to take the second appellant to see Tuan Mat Zaraai ( “kerana saya diarah untuk membawa Sukma untuk berjumpa dengan Tuan Mat Zaraai “). Asked whether it was fixed, he said he did not know. He said that after that he met the second appellant on 9, 10, 16 and 17 September 1998 but he was not present during all the interrogations. He admitted that on 9 September 1998 the second appellant was examined by Dr. Zahari Noor (TDW5) who also examined the second appellant’s anus and that he (ASP Rodwan) instructed that photographs be taken. He denied that when he took the second appellant to see the magistrate to have his confession recorded he told the second appellant that he would be released the following day if he made the confession.

Crossexamined by Mr. Karpal Singh why the second appellant was remanded for 14 days he said it was to investigate further regarding the second appellant’s homosexual involvement and to look for witnesses.

Coming to the day the second appellant was charged in court in respect of Criminal Case No. 6213598, ie, on 19 September 1998, ASP Rodwan admitted meeting Zulkifli Nordin, an advocate and solicitor who wanted to meet the second appellant. He also admitted that Ganesan (TDW4) had also tried to meet the second appellant during the latter’s detention but was not successful. He admitted that Ganesan had written to him, telephoned him and even saw him on 10 September 1998 for that purpose but he did not allow Ganesan to meet the second appellant.

Reexamined by the Deputy Public Prosecutor, he said that on 19 September 1998, the second appellant’s counsel was Mohd. Noor Don.

The next witness called by the prosecution was ASP Zulkifli Mohamed (TRW4). He accompanied ASP Rodwan to get the remand order on 7 September 1998. He denied all the allegations made by the second appellant against him, mentioned earlier.

We now go to the rebuttal witnesses called by the prosecution. The first rebuttal witness was SAC1 Musa bin Hassan (TRW1). He said that at about 9.30am. on 18 September 1998 he met the second appellant. He told the second appellant that he would be charged under s. 377D of the Penal Code. He showed two letters from Ganesan (TDW4) and asked him whether he would like to appoint the solicitor who wrote those letters. He also showed the second appellant call cards of lawyers for him to choose. On the same day at about 4.30pm he arranged for the second appellant to contact Encik Mohd. Noor Don, by telephone. Mohd. Noor Don came to see the second appellant twice. He denied all the allegations made by the second appellant regarding the appointment of Mohd. Noor Don and regarding the charge to be preferred against him and the sentence he would receive.

On 30 September 1998 Mohd. Noor Don telephoned him. He said he wanted to see the second appellant which he did at 3.40pm. Shown the letter dated 30 September 1998 he denied forcing the second appellant to sign it.

Under crossexamination by Mr. Jagdeep Singh Deo, he admitted that he met the second appellant twice ie, on 16 September 1998 and 18 September 1998. He admitted that it was he who instructed that the second appellant’s confession be recorded, after 10 days detention. He agreed that according to Ganesan’s letter dated 10 September 1998, Ganesan was still acting for the second appellant. However, until 18 September 1998 he did not get a confirmation about Ganesan’s appointment. Neither did he contact Ganesan. Asked whether it was usual for him to recommend a lawyer to detainees, his reply was “Not necessarily “. He denied that when he saw the second appellant on 18 September 1998, he told the second appellant not to use the services of Ganesan and that if the second appellant were to plead guilty he would only be sentenced to three month’s imprisonment. He admitted that the second appellant’s sister met him when the second appellant was under remand. Asked why he did not ask the second appellant to get his sister to engage a lawyer for him, he replied that the second appellant was under investigation. Asked whether the second appellant was still under investigation on 18 September 1998, he said “No “. He also did not provide the second appellant the facility to contact his sister for the purpose of engaging a lawyer. He admitted he was in court throughout the proceeding on 19 September 1998 and he met Zulkifli Nordin who informed the court that he was acting for the second appellant. Asked whether he knew that the appointment of Mohd. Noor Don was disputed ( “dipertikaikan “), he replied that the appointment of Mohd. Noor Don was not disputed. He was then shown the notes of evidence of the Criminal Case No. 6213598. The record reads:

En. Zulkifli

Keluarga OKT melantik saya untuk mewakili OKT. Keluarga OKT X kenal P/OKT. Keluarga OKT mempertikai perlantikan Encik Mohd. Noor Don. Minta izin bercakap.

(My translation

The accused’s family has appointed me to represent the accused. The accused’s family does not know the accused’s lawyer. The accused’s family disputes the appointment of Encik Mohd. Noor Don. I ask for permission to speak.)

SAC1 Musa was then asked whether the record was wrong. He said “I don’t know. ” Put to him that Mohamed Noor Don’s appointment was disputed. He replied “No “. He admitted that according to the record Mohamed Noor Don asked for one day’s imprisonment but denied that it was the same as ( “selaras dengan “) what he had informed Mohamed Noor Don.

Shown the letter dated 30 September 1998, he said he did not know who typed the letter, but on that day Mohd. Noor Don did meet the second appellant at Bukit Aman. He denied it was typed on his instruction.

He was further crossexamined by Mr. Karpal Singh. He admitted that in 1997 he investigated the allegations ( “tohmahantohmahan “) against the first appellant. He did not carry out a full investigation in 1997. However he admitted that he recommended that no further action be taken on the file and that a full investigation be carried out first before such recommendation be made. He also admitted that he made similar recommendation to the Attorney General who agreed with him. The file was however reopened in June 1998 based on the police report by Mohd. Azmin Ali concerning the book “50 Dalil “. The following question and answers read:

S: You arranged for a meeting in your office between Mohamed Noor Don and Sukma?

J: Benar, pada 30.9.98.

S: Sebelum tarikh ini, Mohamed Noor Don belum dilantik.

J: Saya setuju.

S: You allowed the use of your office by Mohamed Noor Don to see Sukma.

J: Yes.

He admitted that the second appellant was a timid person and “most probably ” was prone to be more susceptible to breaking down. He was aware of the beating of the first appellant by the Inspector General of Police. He was aware that the second appellant was not questioned within the first 24 hours. He agreed that a statement from the second appellant was videotaped and it was something new. He admitted that he was given a copy of the second appellant’s confession on 17 September 1998 by ASP Rodwan (at 6pm).

Under reexamination by the Deputy Public Prosecutor, he explained that he recommended the investigation against the first appellant to be closed in 1997 because the first appellant called him to his office and handed to him letters purportedly signed by Ummi Hafilda and Azizan to the effect that they had withdrawn the allegations ( “tohmahan “) against the first appellant and directed him to close the investigation as the allegations were unfounded. Regarding the meeting with Mohamed Noor Don he said it was the latter who contacted him. He said the investigation was completed on 17 September 1998 after he received the confession. He denied it was he who appointed Mohamed Noor Don to act for the second appellant.

The second rebuttal witness was K/Insp. Sampornak Ismail (TRW2). He said that on 7 September 1998 at about 3pm he was told by ASP Rodwan to interrogate the second appellant. He carried out the interrogation with five other officers (D/Kpl. Ahmad Bustami (TRW3). D/Kpl. Mokhtaruddin (TRW5), D/Kpl. Hamdani (TRW4), Lee Tuck Seng (TRW7) and Tan Hwa Cheng (TRW6). He was the leader of the team. The interrogation started on 8 September 1998 and completed on 15 September 1998 onwards, he was assisted by three detectives. The interrogations were conducted from 9am to 12.30pm and then from 2pm to 4.45pm. He admitted that at the beginning of the interrogation on 8 September 1998 he asked the second appellant to remove his shirt and trousers to examine whether he had any injury which was a normal procedure. He denied all the specific allegations made by the second appellant which I need not repeat eg, the kicking of the chair, the knocking of his spectacles, the scolding, the threat etc.

Crossexamined by Mr. Govind Singh Deo, he agreed that the interrogation was in respect of the book “50 Dalil ” which he had not seen but was given pp. 63 and 64 by ASP Rodwan. Asked who else was mentioned in the book, he replied if he was not mistaken another person by the name of Azizan was also mentioned. Asked whether any other name was mentioned he said he could not remember. Asked whether it was a high profile case, he said he did not understand the meaning of high profile. When explained to him he said “Now I understand “. Pressed further whether he now knew the name of a “famous person ” ( “orang yang terkenal “) mentioned in the said pages given to him, he replied: “Now I know – Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim. Before the interrogation, I did not know. ” Asked for how long the second appellant was completely undressed on 8 September 1998, he said about four minutes. He admitted that he and four other officers repeatedly questioned the second appellant, but not simultaneously. He denied all the specific allegations made by the second appellant. He repeated that the purpose of the interrogation was to obtain “intelligence statement ” which means “risikan keselamatan negara ” as instructed by ASP Rodwan.